Separating the Forest from the Trees

Scaling Your Organization for Success

As companies go through phases of growth and decline, innovation and stasis, integration and diversification, resource needs fluctuate in terms of numbers, types and capabilities. Even for eminent companies such as du Pont, General Motors and Sears Roebuck, these cyclical phases have more often than not resulted in – as the professor of business history, Alfred Chandler, once wrote – “Resources accumulated, resources rationalized, resources expanded, and then once again, resources rationalized.”1

It is an unfortunate reality that the “resources rationalized” part, more often than not, relates to reducing headcount. How best to achieve that is a common source of questions from clients, often hoping for some magical thinking that will enable a rapid and relatively painless outcome. The reality, however, rarely matches those aspirations but not because of a lack of possibility, more because of a lack of method.

QUICK READ

Key takeaways:

- Determining the types and sizes of particular resource groups required in the short term versus those likely to be needed in the longer term is a challenging task when faced with the need to undertake a rightsizing transformation. This speaks to the importance of finding the right balance between strategic potential (“doing the right things”) and tactical details (“doing things right”).

- A lack of access to adequate data or an understanding of the reasoning behind why things operate as they do only add to the challenge. This is often compounded by variance in job roles and responsibilities across organizations.

- Ultimately, though, there is a finite set of ways to look for savings opportunities, but unless changes are made to the flow and volume of work in the business, none of the savings will stick.

- Once identified, savings should be prioritized so that a properly managed transformation program can be established to ensure objectives are achieved without upsetting key growth or innovation initiatives.

MORE DEPTH

ASSESS THE LANDSCAPE FIRST

The need for rightsizing is usually for financial reasons resulting from business integration, depressed demand or a need to increase investment in innovation or operational expansion. It is not my intention here to dig into motives or what some might see, per Barack Obama in his recent biography, as “the corporate world’s preference for cost cutting and layoffs over long term investments as a way of boosting short-term earnings”2. However, the question of what and how much of particular types of resources are needed to meet the demands of a set of currently pressing circumstances, versus what may be needed to meet longer terms objectives, are often at odds with one another.

To develop the best course of action, leaders must step back and understand the broader picture, while recognizing that without adequate “accurate and meaningful data and without clear-cut lines of communication and authority, they [leaders] are forced to allocate present and future resources in a haphazard and intuitive way.”1

So, there are two challenges that often complicate even getting to the start line that need to be addressed if credible progress is to be achieved:

- Inadequate, hard to access, or unavailable data – this can derail timelines and test the patience of senior executives who are confronted by the consequences of multiple or inadequate systems providing inconsistent data that complicates and prolongs the analysis. Moreover, in organizations with distinct business units, it is common to find that job descriptions, decision rights and accountabilities are rarely standardized across the corporation. This makes comparison of individual and team metrics and productivity across business units arduous or impossible. Result: more time and effort than anyone expected or wants to expend digging through the organizational bureaucracy searching for accurate, reliable and relevant information.

- Understanding reality – understanding why things are done the way they are and how they might be changed requires the involvement of people close to operational reality. Again, this can be a source of frustration because it takes them away from their day jobs and adds to the timeline and risks exposing the project to the organizational grapevine with all that entails. However, involving the right people at the outset can save time aplenty on the backend in terms of viability of decisions and organizational buy-in.

In assessing the landscape, consideration must be given to the longer-term implications of reductions that can result in unfortunate consequences. An extreme example of this (in terms of consequences) can be seen in the recent case of the network management technology company Solar Winds “where common security practices were eschewed because of their expense.”3. The need for a rational, information-based process is paramount – bringing credibility to decisions and practical ways to implement them.

Nevertheless, once the data has been obtained and analysis undertaken the focus needs to be on reality and not the tempting distractions of wishful thinking. This is a simple, but fundamental principle that is often overlooked. Essentially, there are 3 core courses of action open:

Ultimately, savings have to come from stopping doing things, streamlining them to improve efficiency, or shifting to a lower cost environment or different cost bucket. Just reducing headcount without ensuring one or more of these has happened merely increases pressure on individuals and the organization as a whole and is likely to result in dissatisfaction levels increasing and/ or employee numbers (and, therefore, costs) over time growing back to where they were at the outset.

STUDY THE FOREST BEFORE THE TREES

In the search for a workable and urgent solution, it is easy to jump into the details too quickly and lose sight of the proverbial forest. The distinction between what is needed now versus the future is knowing what operating actions are required (“doing things right”) and what strategic moves should also be considered (“doing the right things”)4

I have seen too many companies initiating huge efforts jumping into the details before they are ready, searching among the trees, before realizing that, done too early, looking tree by tree is a painstaking, slow and ultimately unrewarding strategy. They were better served when they stepped back, looked at the wood as a whole, and considered the strategic opportunities that existed. Only then should they have returned to considering the trees again – a considerably more productive and efficient approach. The forest or strategic opportunities (“doing the right things”) are not an abstract set of ideas, but rather a practical start point for thinking big at the outset:

- Restructuring at the top releases opportunities to reset thinking on whole areas of business. For example, breaking up or combining business units or getting out of a particular product or business line.

- Small percentage changes in operations often provide much bigger savings than similar percentages applied to support functions because their scale is usually so much larger and because previous efficiency programs have likely focused repeatedly on squeezing support functions.

- Rethinking the role of the corporate center (or its equivalent in a BU) although this is often a protected species given its proximity to the C-suite. Clarifying the role of the center in terms of providing obligatory functions, centralized services, or value creation5 is a good place to start. Applying tests of value and the quality of services provided by the center can redirect and streamline the energy and scale of what is required and where the work gets done.

- Focus on bending the cost curve relative to profitability or revenues rather than focusing on absolute targets for cost reduction. This approach works well for a growth company and allows costs to become more justifiable over time, without the disruptive effects of a classic cost take-out too early in the growth cycle.

TEN PATHS TO CONSIDER

Once the rationale and scale of savings required have been clarified, the facts are available, the strategic opportunities have been appraised, the next step is to look at the trees (“doing things right”). Again, there is no magic solution here, but rather a finite number of ways to look for savings. Added up, they can create a substantial number of opportunities:

- Centralize/ Share Services – combining groups that are undertaking similar types of work (e.g. project management, planning groups)

- Eliminate activity overlaps – clarifying roles, decision rights and handoffs to remove double work (e.g. product management and product marketing assessments of market opportunities)

- Stop or reduce activities – eliminate non-strategic or low value-add projects, activities and processes (e.g. removing the long tail of small projects with low ROI from budgets and plans)

- Leverage lower-cost locations – moving work to areas where costs are lower (e.g. internal shared services such as development of training courses)

- Insource or Outsource – increased use of specialized and more efficient platforms for higher volume, often more transactional work at scale but highly specialized in other cases. Most often this involves an external vendor, although sometimes benefits can be achieved by bringing resources back in-house when outsourcing has provided less than expected benefits (as did Target Corporation when it brought technology capabilities back in house after its 2013 data breach)6

- Automate and Redesign Processes – utilizing technology and rethinking business processes to simplify and streamline work and reduce headcount requirements (e.g. Agile work methods, automated customer support bots, Robotic Process Automation)

- Expand oversight spans and/or reduce organizational layers – restructure the organizational design to expand oversight responsibilities and limit numbers of supervisory layers (e.g. establish guidelines and KPIs for supervisory spans taking account of different types of functional and organizational level requirements)

- Increase goals and output expectations – Raise KPIs and targets to increase productivity expectations (e.g. sales goals, procurement dollars managed, number of audit completions)

- Optimize employee benefits – Adjust employee benefits to match external benchmarks.

- Clarify decision rights, roles and responsibilities to speed up work -low and productivity.

This is not an especially long list, but it is fairly comprehensive. As previously noted, to effectively and judiciously leverage these types of opportunities requires access to data as well as the involvement of people who really know the details of how the organization operates… without being wedded to the past. This might seem to imply a dauntingly expansive stakeholder engagement exercise, and admittedly it does require some competent project management, but these days there are some very effective tools out there that can act as accelerators to gaining insights and providing short-cuts to validation, such as that provided by Agreed.io.

REMEMBER, NOT ALL TREES ARE THE SAME

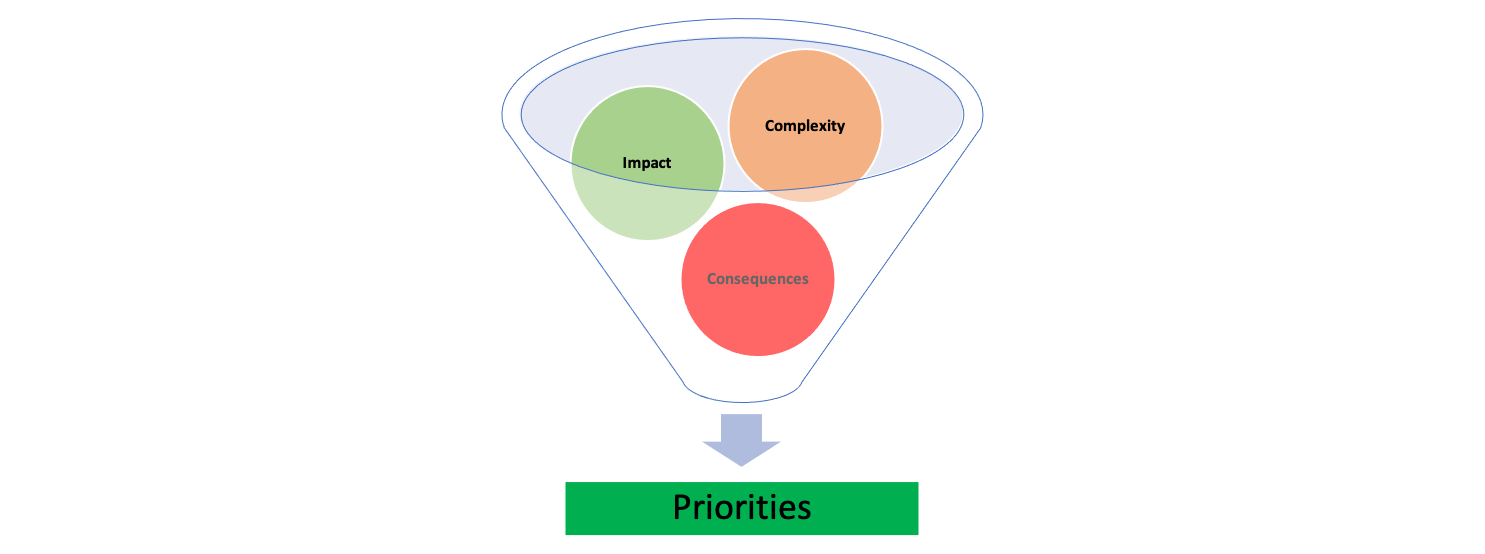

Not all the opportunities will be equal, so the next task is one of sifting which ones to prioritize for immediate versus longer term action. A simple matrix of financial impact versus complexity (also a proxy for difficulty of implementing) is a good start. But one more component that is often overlooked should be considered: potential negative consequences that should be mitigated against. For example, will a reduction in headcount in a given area expose the company to increased legal risk or delays in new product launch or higher turnover of key staff? Understanding this last point as implementation is planned can save a lot of backsliding later as mitigation strategies or reversals become necessary because of a lack of second-order thinking.

PLAN FOR THE SHORT AND LONG TERM

Finally, once the opportunities have been prioritized and implementation plans developed, the task in the short term becomes one of project management (this article by former colleague Howard Spode is an excellent primer7). It requires a focus on rewiring the organization, reengineering processes, finding the right people, and establishing measures and oversight to ensure there is no creeping return to old practices, or weeds that grow in place of the trees that have been removed.

If you are focusing on strategically managing your people cost structure and talent needs, let’s chat. We can quickly help you see the forest and the trees with insights into where you should be focusing attention. Redwood Advisory Partners has decades of experience supporting clients through the design and implementation of organizational transformation, structural change and talent management strategies. Follow or connect with the founder, Stephen, on LinkedIn (where you can find other articles in this series) or visit www.redwoodadvisorypartners.com. You can contact Stephen directly by email at [email protected]

Thanks to Colin Taylor (https://www.linkedin.com/in/consultcolin/) for his, always helpful, editorial contributions.

Notes

- Strategy and Structure, Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise, Alfred D. Chandler

- A Promised Land, Barack Obama

- As Understanding of Russian Hacking Grows, So Does Alarm, NYT Jan 2, 2021

- Turnaround Strategies, Journal of Business Strategy, Charles W. Hofer 1980

- The Corporate Headquarters in the Contemporary Corporation: Advancing a Multimarket Firm Perspective, Markus Menz et al, 2015

- https://www.laserfiche.com/ecmblog/companies-jump-on-it-insourcing-bandwagon/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ten-life-hacks-project-managing-transformation-bpo-howard-spode/

Leave a Reply